In art, I neither admit nor omit one thing over another. Are light and colour not life? Form, physiology, and psychology of animate or inanimate things, are they not also life? For what reasons do you want to persuade me to radically separate things when there is only one body? Paint a landscape that is poetically correct in terms of lines, perspective, and truth, but if you do not take into account the accuracy of the light, the brightness of colour, you do not give me a complete piece of truth, the precise sensation of that natural scene that you wanted to reproduce for me. (…) It is therefore preferable for a work of art to possess all these qualities, even if they are faint, but that indicate a conscientious search for truth in all its relationships, rather than a work that excels solely in colour or form.

June 1897. Giovanni Battista Ciolina’s diaries. Transcribed by Paolo Ciolina

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

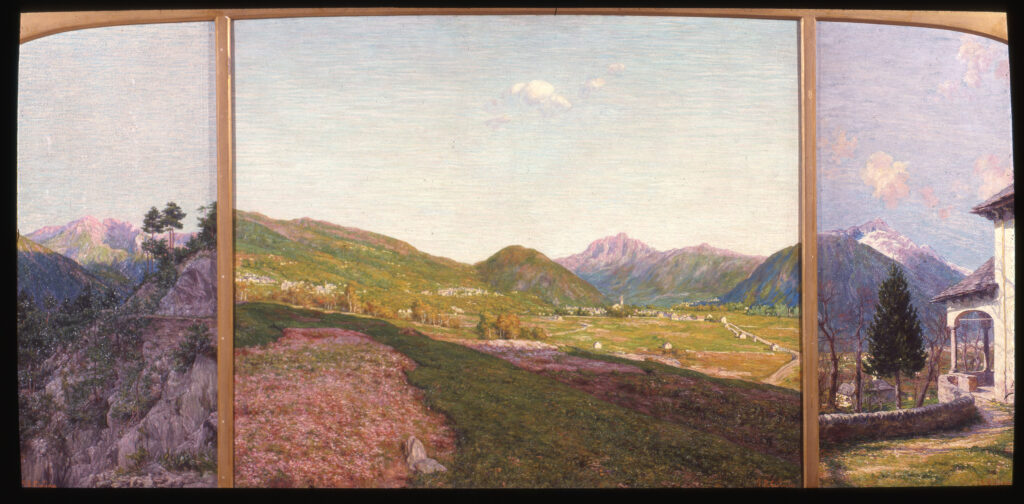

In Ciolina’s work, it is rare, if not unique, that a landscape is completely devoid of figures, either human or animal. From the epic symphony of Il ritorno dall’alpe (The Return from the Mountain) to La raccolta delle patate (The Potato Harvest – tappa 5), from Toceno al tramonto (Toceno at Sunset – tappa 4) to Cadono le foglie (Falling Leaves – tappa 10), to name just a few, the landscape is never empty. This is instead the case with Trittico della valle (Valley Tryptych), created in 1923 for the Milanese lawyer Ortis, who perhaps had the opportunity to admire Il ritorno dall’Alpe at the home of the engineer Caproni and wanted to have something similar. In 1986, Aurora Scotti observed that “the formula of the triptych is related to a motif… which had great success at the end of the 19th century,” mentioning Segantini, Morbelli, Pellizza and other divisionist artists. It is no coincidence that Trittico and Il ritorno dall’Alpe are among the works that come closest to Divisionism, though they do not strictly adhere to it, especially in the absence of primary colours. In fact, by the 1920s, Divisionism had been largely surpassed by the artistic trends in Italy and Europe, and even by Ciolina himself. He had long moved away from a mere ‘photographic’ reproduction style, adopting a more constructive and chromatically free brushstroke. The divisionist approach, I believe, was revisited by the artist explicitly at the request of the client for the Trittico della valle.

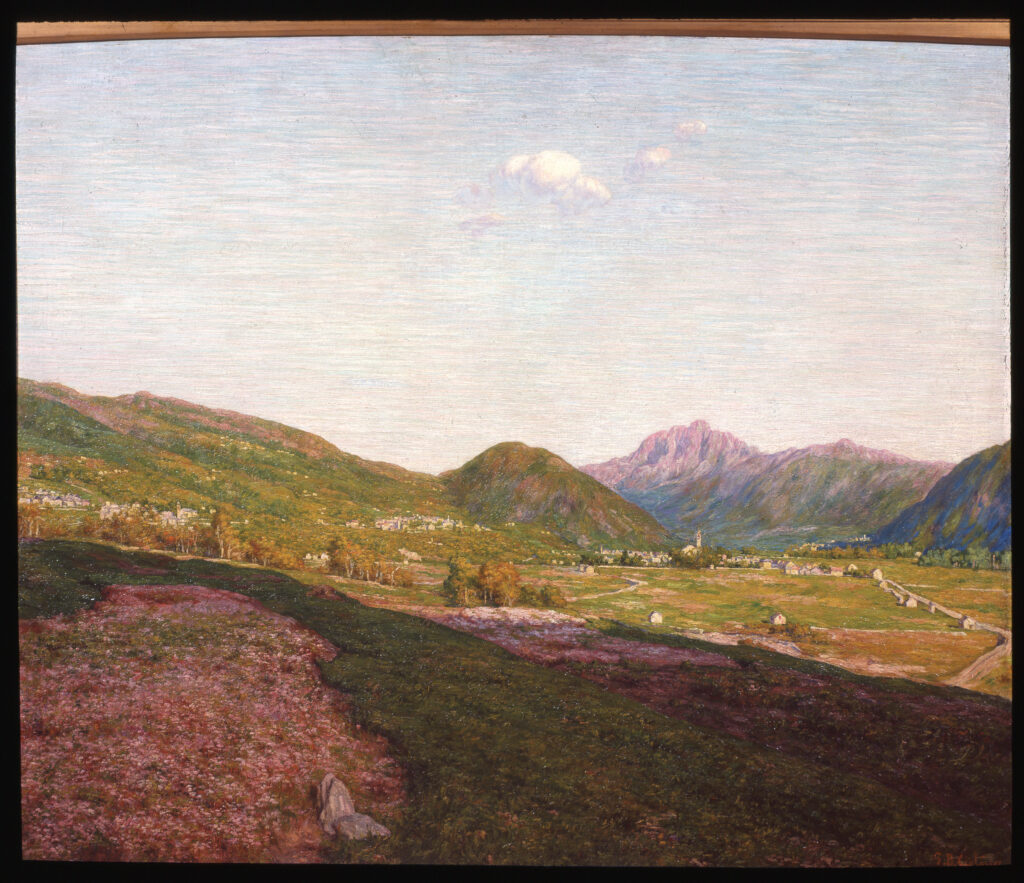

There is an animated version of the large central panel, created for the Piazza di Craveggia family, in which Ciolina added a light-coloured cow in the foreground, the woman-child couple that opens the caravan of Il ritorno dall’Alpe, albeit in a slightly different pose, and a man in a white shirt with a cape over his shoulders. Both versions provide a broad view of the valley from the height of Buttogno, which is unusual for him, as he usually preferred his viewpoint from Toceno. In the animated version, he skilfully constructed the foreground with the hill shaded by an invisible cloud that intercepts the intense, clear light of a summer afternoon. There are two predominant colours, greens and purples, with the latter dominating, from the flowery patch in the foreground to the extreme ridges of the Gridone. The purples then evenly streak the sky and the shadowed part of the solitary little clouds that sit high in the centre. The typical structuring of light and dark planes, not necessarily based on light and shadow, creates a monumental effect, even though the canvas is not as immense in size as Il ritorno dall’Alpe. It conveys peace and an atavistic idyll that the valley no longer possessed at that time (in that year the Domodossola-Locarno railway was inaugurated, of which there is no trace in the painting). The application of minute touches of colour, which also characterises La raccolta delle patate (tappa 5), covers a large part of the canvas, achieving an intense, vibrating effect, especially in the vast flowery spot in the foreground, capable of capturing light even where there is shadow. The arrangement of colour in more or less delicate filaments is instead reserved for the distant mountains in the background: In Brun, Gridone and the slope of Mount Bassetta, which partially conceals Malesco and is uniquely treated with dark blue brushstrokes to evoke the shadowy freshness of the dense, opaque forest.

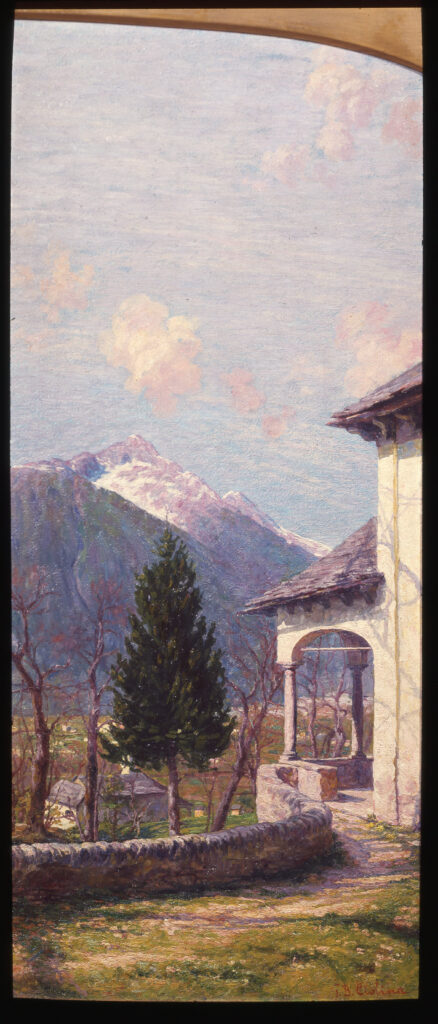

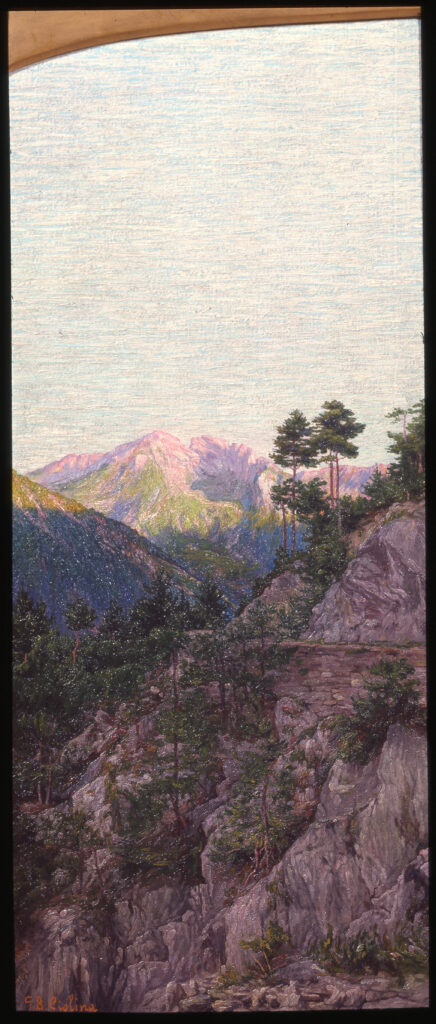

The wide view is contrasted in a meticulously balanced way by the subjects of the two side ‘wings’, creating a structure that is reminiscent of a Flemish altarpiece, even though they are fixed: two limited yet extremely realistic glimpses. The first, on the left, shows the Arvogno Valley in violet shadow, with the Scheggia peak shining in the background, lit by the early morning light, and imbued with a romantic essence reminiscent of Turner or Friedrich. The only trace of human development is seen in the supporting wall of the road. The second, on the right, features the porch of the Madonna del Sasso oratory, serving as a backdrop to a springtime view of the valley towards the Pizzo Ragno. It is constructed once again with alternating light and shadow, where the small wall, the shadow of the porch, and the dark mass of the spruce tree in the background take centre stage. There is no doubt that the combination of the three views is permeated by an intense poetic vein that the artist felt deeply. However, it is also clear that, given the technique used, it is primarily shaped by the client’s taste. It is enough to compare the Trittico della valle with La raccolta dei grilli (The Collection of Crickets – tappa 8), which is slightly earlier (around 1918), to see the difference.

Text and image research and adaptation by Chiara Besana.

Critical analysis by Paolo Volorio.

Sign up to receive news on events, exhibitions and trainings from the Rossetti Valentini School of Fine Arts Foundation.

Iscriviti per ricevere le news su eventi, mostre, incontri di formazione organizzati dalla Fondazione Scuola di Belle Arti Rossetti Valentini.